Losing Jennifer

Sandy:

Exploring Group

Consciousness Effects on Random Events

During a Local

Tragedy

BRYAN J. WILLIAMS

Department of Psychology

e-mail: [email protected]

September 3, 2002

Dedicated in

memory

of

Jennifer T.

Sandy

(September 18,

1977 – August 29, 1998)

Introduction: Personal loss

as

a conscious “candle in the dark?”

Only you, cared when I needed a friend,/Believed in me through thick and thin.../God bless

you/You

make me feel brand new/For God blessed me with you.../Precious friend, with

you

I’ll always have a friend.../You’re someone who I can depend to walk a path

that sometimes bends.../How can I repay you for having faith in me?/...Oh,

God

has blessed me, girl.../God has blessed me with you...

- Simply Red, “You Make Me Feel Brand New” remake (2003)

Jennifer Sandy was a kind, brave, and beautiful soul whose life was suddenly and tragically taken in a high-speed motorcycle accident in the early morning hours of August 29, 1998, at the youthful age of 20. She was a terrific athlete, full of vitality and drive, who was most noted for leading the Sandia High School Lady Matador varsity basketball team to a AAAA state championship in February 1996, the first that the school had ever achieved in years. She had also played in the varsity softball team, as well. Off the field, she was a warm, positive, and fun person to be around, something that seemed subtly apparent as a subjective feeling in her presence that seemed to radiate from her. Thus, as a result of her many athletic accomplishments and her outgoing personality, Jennifer touched many lives and had a wide network of friends from all different social levels. I learned later on that she had the potential to touch many more lives by becoming an E.M.T., which she was attending the University of New Mexico for at the time of her passing. So it was a great shock and a personal loss to many when word of her passing had rippled outward to affect the miniature “noosphere”-like circle of family, teammates, and many, many friends that she had throughout the state of New Mexico and the entire Southwest United States region.

I had personally known Jennifer ever since middle school, and following high school graduation in May 1996, had not seen her for two years. She was a special friend to me because she was one of the few people at a higher social level who actually cared when I was isolated in my own life. As if sensing I needed a friend nearby, she would willfully approach me, flashing her lovely smile as she greeted me warmly and sharing her kind-hearted and joking personality to lift my spirits. She accepted me as an equal despite any social repercussions this might have had on her, and so she deeply meant something to me, something I gradually came to realize during the course of our friendship but never had the courage to tell her when she was alive. I had the highest hopes of seeing her again sometime in the future, but sadly that day never came, and although I barely showed overtly to anyone at the time, I was devastated by the news of her death.

Because of this warm effect she seemed to have on people, Jennifer seemed to me to be the best example I could give of someone possessing a personal consciousness “field,” and so when she unexpectedly passed, I thought this metaphorical field she had, as well as those of the countless other individuals in her circle, might continue to shine bright with hope like a conscious “candle in the darkness of tragedy” in the days following, bringing all those near and far into a wider “group consciousness” of sorrow, reflection, and support. I hypothesized that this mass group consciousness would be coherent enough that it would be capable of moving random physical systems in manner similar to that seen in preliminary experiments conducted at that time which were suggestive of correlations between human social coherence and anomalous statistical deviations from chance in purely random data (Nelson et al., 1996, 1998a; Radin, Rebman, & Cross, 1996). A tentative interpretation of these anomalous deviation patterns is that they might represent the statistical signature of a possible nonlocal mind-matter interaction effect that may be associated with the developing group consciousness.

In observation of the fourth-year anniversary of her passing, and in order to explore the above hypothesis at a basic level, I decided to carry out a special exploratory “memorial” analysis of the data collected by the first Internet-based, globally distributed network of random number generators (RNGs, also called “EGGs”) established and monitored by the Global Consciousness Project (GCP) (Nelson, 2001). At the time of Jennifer’s passing in August 1998, the GCP had just been founded and the global RNG/EGG network had only been running for a little less than a month, still going through test trials and containing only 5 active RNGs/EGGs running either in the Eastern United States or in Europe. I feel strongly that looking at Jennifer’s data would be valuable because of the number of people that she touched and the kind of warm-hearted, caring attitude and presence that she possessed, someone with whom the concept of a personal consciousness field might seem more sensible. From a purely scientific standpoint, it also provided an unfortunate but unique opportunity to examine the field consciousness effect during solemn group events like the loss of a loved one, memorial services, and funerals, all of which tend to show unified displays of attention and the singular emotional expressions of grief. Previous experiments suggest that both focused attention and emotional expression may be associated in some way with the field consciousness effect (Bierman, 1996; Blasband, 2000; Nelson et al., 1996). Preliminary explorations of these kinds of events by the GCP seemed to produce results that were promising and potentially meaningful (Nelson, 2000). In addition, it might provide additional insight into the issue of a possible “experimenter effect” on the part of myself and the other researchers involved in the GCP that might permeate the global RNG/EGG data from time to time (Kennedy & Taddonio, 1976; White, 1976).

I realize that there might be some people that may look at this analysis and regard it in this context as being disrespectful to Jennifer’s memory. However, I wish to emphasize a point quite to the contrary. As I attempted to lay out above, my motivation for carrying out the analysis was meant to be far from being disrespectful to Jennifer in any way, and I apologize if some think that that is my intent here. Rather, I wish to honor her, both for what she meant to me and what she meant to others, by attempting to show that at least some of the mysterious aspects surrounding a personal loss that we always question spiritually may be more fundamental to the relationship between mind and matter than we might realize, and that Jennifer represents a special example of this.

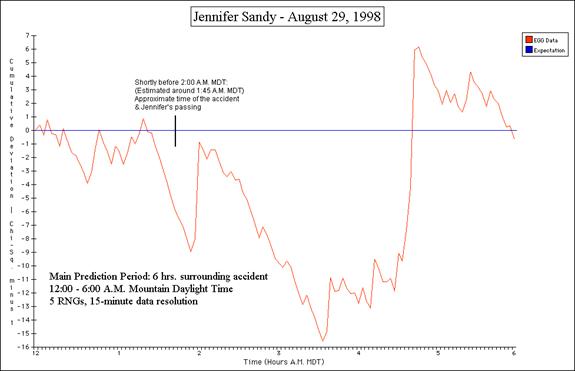

Cumulative Deviation of Chi-Square: The Accident & Jennifer’s Death

For the primary analysis, I followed the standard GCP procedure of working the data using Chi-Square measures cumulatively compounded to represent an overall deviation from mean chance expectation in the global RNG/EGG data (for extensive details on the process, see Nelson, 2001). Under ordinary circumstances, we would expect the behavior of each of the global RNGs/EGGs to be perfectly random from each other and their deviation from chance almost exactly at zero, based on the inherent nature of a noise-based truly random number generator. It seems that when events that greatly affect us occur, the global RNGs/EGGs tend to deviate from randomness and show anomalous patterns in the data that are beyond chance expectation. This is what the Chi-Square technique is intended to measure quantitatively, and the Chi-Square result for the accident and Jennifer’s death is shown in Figure 1. According to a local newspaper report (Journal Staff Report, 1998), the accident occurred shortly before 2:00 A.M. Mountain Daylight Time (MDT), August 29, 1998 [Note added: according to more recent estimates provided by Jennifer’s mother Loretta following the completion of the analysis, the Albuquerque Police estimate the time of the accident at around 1:45 A.M. MDT]. With the given time changes, this corresponds to 8:00 in Universal Coordinate Time (UTC). Based on this, I formed a prediction period surrounding this point in time, running from 12:00 - 6:00 A.M. MDT (6:00 - 12:00 UTC), by using the GCP prediction protocol for unpredictable events (Nelson, 2001). This prediction period adds two hours before the accident as a “pre-response” period, and concludes 4 hours after as an accident “aftermath” period. The former period would make it possible to determine if there was any pre-event change in the RNG data that started prior to the accident or even at the moment of the accident itself, while the latter period measures any lingering deviations that may have been generated as a result of the accident, as well as any deviations that are just being generated as a growing number conscious minds suddenly become aware of what happened and emotionally react to Jennifer’s passing as the news spreads with increasing time.

Figure

1. Cumulative deviation of

Chi-square result for the 6-hour prediction period of the accident, 12:00 -

6:00 A.M. MDT (6:00 – 12:00 UTC), August 29, 1998. The approximate time of

the

accident and Jennifer Sandy’s death is indicated with a vertical line along

the

expectation line of zero.

The graph in Figure 1 suggests that the data fluctuates rather strongly, and the final overall value suggests that the cumulative behavior of the data is statistically indistinguishable from a random walk (Chi-Square = 119.3, 120 df, p = .5). However, a closer post hoc examination of the data seem to indicate other things of possible interest, most notably around 4:30 A.M. MDT (10:30 UTC).

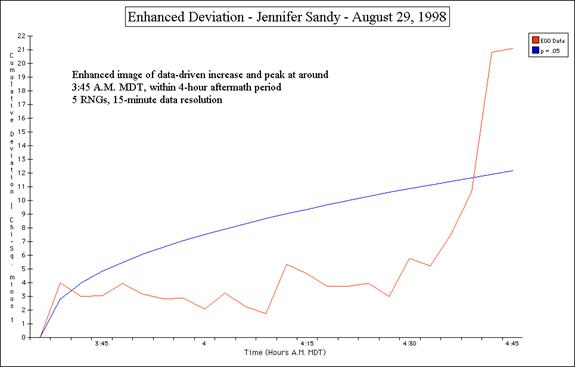

Figure 2. Detailed view of the sharp positive trend at

around

4:30 A.M. MDT, August 29, 1998. The smooth parabolic curve shows the

location of significance at the .05 level as time

passes.

Figure 2 shows the details of a potentially interesting trend that peaked at around 4:30 A.M. It was found that this trend was so vertically steep that it eventually exceeded chance expectation, and if it had been part of an a priori prediction, it would have been highly significant overall (Chi-Square = 44.06, 24 df, p = .007), having odds of about 142 to 1 against being a result due to chance alone [Note: in psychology, we generally accept a statistical value as being reflective of a possible effect when the odds are smaller than 20 to 1, and in this case, the odds would have been much smaller than that]. Adjusting the value using Bonferroni correction for multiple analysis, the result is still associated with a probability of .029, or having odds against chance of about 33 to 1.

Incidentally, it is interesting to note that this time between 4:30 and 5:00 A.M. corresponds to the approximate time that Jennifer’s immediate family was notified by the police of the accident and her resulting death, according to information provided to me by Jennifer’s mother Loretta. It is often difficult to know how genuine the finding is or what it could really represent based on the ambiguities in interpreting random data streams, but from a subjective standpoint, it is tempting to wonder whether it might be a meaningful reflection of the reaction to the news by Jennifer’s family and the rest of the individuals within her miniature “noosphere”-like circle.

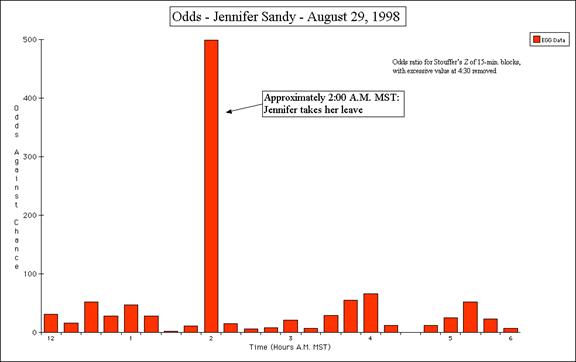

Composite Deviation: Another look at Jennifer’s Death

As a supplemental analysis to the Chi-Square one, I collapsed the individual z-scores across the global RNGs/EGGs into a single Stouffer’s Z-score for each 15-minute period, and then determined the odds ratio for each Z-score to see how likely that each one is due to chance alone.

Figure

3. Associated

two-tailed odds against chance for the 15-minute Stouffer’s Z-scores

during the 6-hour prediction period for the accident and Jennifer’s passing,

12:00 – 6:00 A.M. MDT, August 29, 1998.

Figure 3 displays the resulting odds ratio for the Stouffer’s Z-scores for the 6-hour prediction period I made for the accident and Jennifer’s passing. As can be seen in the graph, one of the most extreme scores strikingly occurs at 2:00 A.M. MDT, around the time of Jennifer’s passing, with a Stouffer’s Z = 2.84 (p = .002). The odds associated with this Z-score are quite high, peaking at around 499 to 1 against chance.

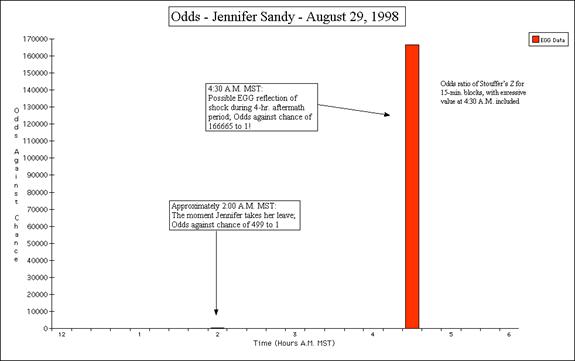

Figure

4. Associated

two-tailed odds against chance for the 15-minute Stouffer’s Z-scores

(with the extreme value at 4:30 A.M. included) during the 6-hour prediction

period for the accident and Jennifer’s passing, 12:00 – 6:00 A.M. MDT,

August

29, 1998.

Figure 4 shows the same result as in Figure 3, but with an extreme value at 4:30 A.M. included. This value was so extreme that I had to remove it from Figure 3 because it basically obscured the other notable value seen in Figure 3. During this time, the 5 global RNGs/EGGs were so highly correlated with each other that it had a Stouffer’s Z-score of 4.37 (p = .000006), which has odds of approximately 166,665 to 1!! This value corresponds well with the sharp trend seen in Figure 2, and is likely to be what was driving the data so sharply.

The significance of this 4:30 anomaly can be put into better perspective by taking a fuller contextual look at the Stouffer’s Z-scores (sign-corrected) for the entire MDT day of August 29, 1998. Figure 5 shows this, with the 4:30 anomaly highlighted in a red box. In this graph, values between the range of +2 and –2 are likely to be due to noise filling the global RNG/EGG network, while any values outside this range are statistically interesting.

Figure 5. Block Stouffer’s Z-scores

(sign-corrected) across global RNGs/EGGs for each 15-minute period of the

full

day in Mountain Daylight Time, August 29, 1998. The extreme value at

4:30 A.M. is indicated with a red square box around

it.

Figure 5 indicates that, while there are several instances throughout the day in which the Z-scores exceed the +/- 2 range, the 4:30 “spike” value in the red box is clearly the most interesting of the entire day, being nearly 4 standard deviations away from chance expectation at zero (p = .000076). Even after Bonferroni correction, the result remained significant at p = .035, or odds of about 28 to 1 against chance. The logarithmic odds against chance associated with these Z-scores are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Two-tailed log odds against chance associated with the Z-scores shown in Figure 5 for the entire MDT day, August 29, 1998. The extreme value at 4:30 A.M. is indicated with a red square box around it.

Figure 6 again indicates that the 4:30 extreme value is the most interesting one of the day, having odds of about 13,000 to 1 against chance alone! This finding also corresponds well with the sharp peak seen in Figure 2. In the two findings being complementary to each other, they both suggest that this anomaly at 4:30 A.M. is not a statistical fluke, and that something clearly moved the global RNG/EGG network at that moment. Again, although it is difficult to know for sure, one wonders whether it might be reflective of the momentary “shock” rippling across the group consciousness that is slowly forming between Jennifer’s family, friends, and teammates as they suddenly start receiving early morning phone calls about what had transpired only a few hours before, and what had happened to Jennifer.

Cumulative Deviation of Chi-Square: Jennifer’s Passing in Context

In Figure 7 a wider contextual view of the global RNG/EGG data is taken over the weekend of the tragedy, August 29 – 30, 1998. The small pink tickmark along the expectation line marks the time of the accident and Jennifer’s passing.

Figure 7. Cumulative deviation of Chi-square result for the contextual period of two days following Jennifer Sandy’s death in 15-minute resolution, Mountain Daylight Time, August 29 - 30, 1998. The approximate time of the accident and Jennifer’s death is indicated with a vertical line along the expectation line of zero.

From a subjective standpoint, the image looks rather striking, with a deep, consistently negative trend driving the dataline to smaller values throughout the remainder of the afternoon of August 29, presumably when most people have heard the news and are reacting accordingly. Then, early on the morning of August 30 (around 6:00 A.M. MDT), the trend goes through an inflection and becomes consistently and sharply positive throughout most of the day. When examined on its own, the overall result for the entire day of August 30 begins to approach statistical significance (p = .07, or odds of about 13 to 1 against chance). This subjective view seems to draw what could be a very meaningful picture, perhaps reflecting the deep shock and sorrow over the loss of Jennifer among those within her miniature “noosphere”-like circle, an overall snapshot of the response of the gathering group consciousness as family and friends come together from near and far to share grief and support. Something even deeper than we could realize, at the boundaries between mind and matter, seemed to be forming [Incidentally, my own learning of Jennifer’s passing came sometime between 10 A.M. and 12 P.M. on August 30, while I was reading the newspaper and came across the report (Journal Staff Report, 1998), which in Figure 7 seems to be in temporal proximity to a very sharp increase or “spike” in the data].

Cumulative Deviation of Chi-Square: Jennifer’s Wake Service

Another event relevant to Jennifer’s passing for which a second prediction period of 6 hours was made was Jennifer’s wake service. The obituary for Jennifer that appeared in the August 31, 1998 edition of The Albuquerque Journal gave the time for the wake/viewing ceremony as 3:00 to 9:00 P.M. MDT on September 1 (21:00 UTC Sept. 1 – 3:00 UTC Sept. 2), and this period was taken as the predicted duration for the event. A prediction was made for this event based on the notion that this event would likely show very strong displays of emotion, and the global RNGs/EGGs might “respond” in a similar way.

Figure 8. Cumulative deviation of Chi-square result for the prediction period

of

Jennifer Sandy’s wake service, 3:00 - 9:00 P.M. MDT, September 1, 1998. The

smooth red parabolic curve shows the location of significance at the .05

level

as time passes.

Figure 8 shows the result for Jennifer’s wake service. Even though the overall result is not significant from a statistical standpoint (Chi-Square = 96.44, 108 df, p = .779), the graph seems to show an interesting trend, having a consistent downward direction for most of the period. At around 8:00 P.M., the data suddenly undergoes an inflection back towards the position, which lasts the remaining hour of the period. The subjective impression of the trend seems to be very much in line with the shared grief and sorrow that was probably felt by many that evening, and may again be suggestive of something potentially meaningful at the boundary level of mind and matter from a subjective standpoint.

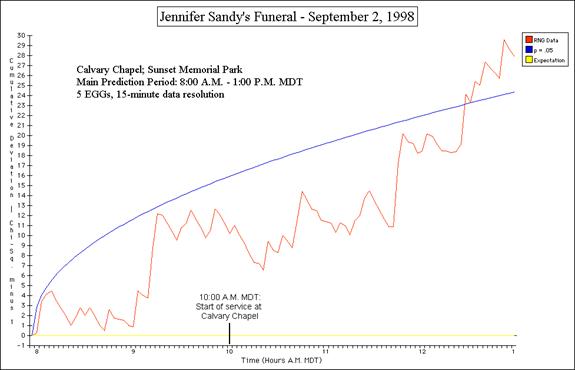

Cumulative Deviation of Chi-Square: Jennifer’s Funeral

A third prediction was made for Jennifer’s funeral service that was held on the week following her death, on September 2, 1998. Since this appears to have been a large solemn group event with hundreds (if not more) people in attendance and sharing the same emotions [Note added: recent estimates suggest that as many as 1,200 people may have been in attendance, exceeding the seating capacity of the chapel], I predicted early on that this event was likely to show the strongest indications of a mass group consciousness “field” effect. It was also an event that I regretfully was unable to attend for personal reasons, but I had thought about Jennifer constantly that morning, and that might have led to a nonlocal attachment on my part to the event. Previous examination of funeral services in the PEAR fieldREG studies that preceded the inception of the GCP seemed to show that the data for such event tended to be negative and nonsignificant overall (Nelson et al., 1998a), although one mass public funeral event for which multiple RNG data was taken [the funeral for Princess Diana of Wales in September 1997] gave a positive and significant result (Nelson et al., 1998b), suggesting that the matter deserved further examination. Based on my intuitions about the service, I thought examine Jennifer’s data to see if anything similar and of interest might reveal itself.

The

obituary for Jennifer that appeared in The

Albuquerque Journal on

September 1 listed the start time for Jennifer’s funeral service at Calvary

Chapel as being 10:00 A.M. MDT (16:00 UTC) on September 2, 1998, which would

be

followed by the entombment of her body in the mausoleum at

Figure 9. Cumulative deviation of Chi-square result of the global RNG/EGG

data

for the prediction period of Jennifer Sandy’s funeral, 8:00 A.M. - 1:00 P.M.

MDT, September 2, 1998. The time of the start of the funeral is indicated

with

a vertical tickmark along the yellow expectation line of zero. The smooth

blue

parabolic curve shows the location of significance at the .05 level as time

passes.

It can be seen from Figure 9 that the data from the global RNG/EGG network had a modest, positive, and gradually increasing non-random slope throughout the morning of the service, which eventually culminates in an overall statistically significant finding (Chi-Square = 127.86, 100 df, p = .031) that has odds of about 31 to 1 against chance. It is also of note that a matching series of simple pseudo-random control data that I generated using a spreadsheet algorithm and analyzed in the same way to compare to this data showed no such unusual trend, and was perfectly random as expected. This made the result for Jennifer’s funeral service consistent with the positive result for Princess Diana’s funeral (Nelson et al., 1998b), and seemed to subjectively suggest that the shared emotional and attentional coherence of all those in attendance had indeed produced something like a mass group consciousness that sad morning. Most unlike the funeral events examined in the PEAR fieldREG studies (Nelson et al., 1998a), Jennifer’s service had shown a decrease in randomness rather than an increase, as though the love, joy, and warmth from her life was still being felt and spread to some degree, beyond the pain of loss. The unified emotions spread that morning were perhaps coherent enough to move the global RNG/EGG network in a very gripping way. This seems to be somewhat further suggested within the context of the entire MDT day, which is shown in Figure 10 below along with the matching pseudo-random data that I created.

Figure

10. Cumulative deviation of

Chi-square result of the actual global RNG/EGG data (blue trace) versus

pseudo-random control data (green trace) for the contextual period of the

entire day of Jennifer Sandy’s funeral, Mountain Daylight Time, September 2,

1998. The starting time of the funeral service is indicated with a vertical

line along the brown expectation line of zero. The smooth red parabolic

curve

shows the location of significance at the .05 level as time

passes.

From Figure 10 it again seems that the actual global RNG/EGG data have a non-random structure throughout most of the morning of Jennifer’s funeral, becoming quite removed from expectation, whereas the pseudo-random control data are level with expectation and nominally random as expected. This also seems to lend some support to the prediction made.

Cumulative Deviation of Chi-Square: One Last Context Look at Jennifer’s Passing

Finally, Figure 11 below shows a large, extended contextual look at the global RNG/EGG data from the five days following Jennifer’s passing, spanning from midnight MDT on August 29 all the way to 11:59 P.M. on September 2.

Figure

11. Cumulative deviation of

Chi-square result for the extended contextual period of five days following

Jennifer Sandy’s death in Mountain Daylight Time, August 29 – September 2,

1998. The approximate time of the accident and Jennifer’s death is indicated

with a vertical line along the pink expectation line of

zero.

The image seems to put the events surrounding Jennifer’s tragic passing into a much larger and very meaningful perspective, with many sharp spikes throughout the 5-day period. It perhaps reflects the strong effect that Jennifer had on the many that she touched in her short life, and that such a touch can move us and even the physical world we live in in a psychologically powerful way.

Discussion and Conclusion: What Could It All Mean?

“Be

as a stone cast upon the water, that the positive

influence of your action may extend far beyond the power of a mere pebble in

the hand of a man.”

-

Ancient saying, quoted in the August 29, 2004 memorial obituary for

Jennifer,

written by her family. (ABQjournal death notices,

2004)

Oh now feel it coming back again,/Like a rollin’ thunder chasing the wind,/Forces pullin’ from the center of the earth again,/I can feel it…

- Live, “Lightning Crashes”

(1994)

Overall, the results described here seem to suggest that there may have been a few modest but potentially notable statistical anomalies present in the data from a global network of random number generators corresponding to events relevant to the sudden and tragic death of Jennifer Sandy. On the surface, these results seem to be consistent with previous GCP explorations of the loss of several notable people such as EGG host Barry Fenn (Nelson, 2000), and with the initial RNG results found during the public funeral for Princess Diana (Nelson et al., 1998b). Although we do not as of yet have a solid theoretical understanding of the process behind anomalies like these, there are several different ways to interpret the findings that may be considered to possibly explain them.

One possible interpretation is that they are due to expected chance fluctuations in the data, given that the data were blocked due to their fragmented nature during the early trials of the GCP global RNG/EGG network. This is an interpretation that can never be completely be ruled out, although some of the results do seem to at least argue against it. This interpretation would especially be valid in cases where deliberate “data fiddling” (in which one might consistently vary the segment size being blocked to fit the fluctuations so that they are purposely larger than they really are) is suspected. It should be noted here, however, that only one segment size of 15 minutes was used throughout, without varying the length, and that this segment size was standard in early GCP analyses using data from this time period. There is also the possibility that errors in data processing created spurious results, although this seems rather unlikely given that matching sets of analyses created both by computer and by hand calculation produced mirroring results. It also may be of some note that there appears to be a close correspondence between the duration of the events relating to Jennifer’s passing and the onset of the anomalous trends in the data, which may be fortuitous but is difficult to ignore given the behavior of the graphs and the statistical results. It must also be recognized that Jennifer’s passing is not the only event to show this close correspondence between the anomalies and event duration; many other events examined by the GCP do seem to show this correspondence as well, and the anomalies occur right where they are predicted to be (Nelson, 2001). Given this finding of multiple correspondences, it is at least arguable that it may be unlikely that the correspondence in Jennifer’s data is simply fortuitous. Thus, it is plausible, but perhaps unlikely, that the potential anomalies in Jennifer’s data are simply expected chance fluctuations.

Another possible interpretation is that the anomalies are due to artifacts generated by extreme physical fluctuations in the surrounding environment. This would include high, localized electromagnetic fields from increased cellular phone, television, and other electronics use around the time of the accident, surges in the electrical power grid, or increased geomagnetic activity. Although this interpretation is plausible, there may be three reasons for thinking that it is rather highly unlikely: 1.) the housings of the RNGs in the network are designed to shield the devices from electromagnetic interference, 2.) the computer power supply to each RNG is usually connected through a surge protector or is battery-powered, and thus often not subject to power surges or blackouts; and 3.) any such extreme physical fluctuation occurring at random in conjunction with the events around the Albuquerque area would likely have been localized to that area, and thus would not have been able to affect multiple RNGs located miles away in other states or other countries. It is also possible that such extreme physical fluctuations could have occurred at random at the locations of the RNG host sites, and thus could have affected their outputs artificially. As a basic check of this with a small number of global RNGs/EGGs in the network at the time, the mean output of 1-bits was checked from August 28 - September 3, 1998 by examining the graphical displays generated in the daily summary data tables available on the GCP website (http://noosphere.princeton.edu). If such fluctuations did occur, one would expect to see outlier outputs, either extremely high (i.e., above 150) or extremely low (i.e., below 70), being consistently given as the mean 1-bit output over long periods of time, which could be indicative of a malfunctioning RNG. However, examination of the daily summary tables revealed no indication of this among any of the 5 global RNGs/EGGs in the network at that time, and each was producing mean outputs well within the expected range around 100 over this period of time, thus basically indicating nominally distributed random data output. Thus, environmental artifacts does not seem be a plausible interpretation for explaining any possible anomalies observed in Jennifer’s data.

Although it is not possible to claim that the results show definitive evidence for it, perhaps one of the most sound interpretations that fits all of Jennifer’s data is that the potential anomalies might represent the statistical “signature” of a subtle mass group consciousness that was forged upon the unified mass attention to the events surrounding Jennifer’s passing and the emotions shared as a result of them. Through this interpretation, the clearest result from Jennifer’s funeral would be consistent with that from the funeral for Princess Diana of Wales (Nelson et al., 1998a), and would therefore suggest that in some cases, solemn group events like mass public funerals can and do show anomalous deviations in line with the group consciousness hypothesis. It is perhaps of incidental note that there seem to be interesting parallels in these two particular cases; Jennifer and Diana were both: 1.) still young and healthy individuals with bright futures ahead, 2.) killed suddenly and tragically in vehicular accidents, and 3.) widely known and admired by large groups of people. Thus, one might speculate that when their lives were suddenly and unexpectedly ended, the losses were devastatingly tragic to many people, and may have in some way been more conducive to group consciousness effects through the widespread “resonance” of affect and mass attendance at their funerals. It is not clear whether the circumstances of the event have any bearing at all on the resulting group consciousness effects based on only two cases, but further comparisons of this nature might perhaps reveal something worthy of note in future field RNG studies of these kinds of events.

As hinted at above, at least some of the results do seem to be in line with a possible correlation between emotional expression and deviations in the RNG output, with the clearest possible indication of this coming from what was presumed to have been the most emotional event of the three identified, that of Jennifer’s funeral. Aside from the possibility that they may be fortuitous fluctuations owing to the nature of a random system, it may perhaps be the case that some of the trends observed in the graphical representations of the data may be an indication (albeit a subtle, indirect one) of this correlation, as well. A possible basis for this argument comes from the results of a previous field RNG study conducted in a therapeutic setting, in which randomness deviations in the RNG were noted in conjunction with defined moments of emotional expression by the patients during their therapy sessions (Blasband, 2000). In that study, the results across several patients seemed to suggest that displays of anger and aggression were correlated with a positive, negentropic trend, while periods of anxious crying were correlated with a negative, increasingly entropic trend.

Based on this, visible trends away from expectation in the graphical results of Jennifer’s data might perhaps carry subjectively meaningful reflections of emotion, given the context of the event. The clearest possible indication of this would perhaps be the trend seen in Figure 8 during Jennifer’s wake service, in which a rather steady negative trend was observed throughout most of the specified period. One might expect such an event to have been one in which much crying and deep sadness was displayed, and thus the negative trend in the data would seemingly be consistent with this kind of emotional display according to the results obtained by Blasband (2000). One might also loosely interpret the extreme peak deviation at 4:30 A.M. on August 29 as being consistent with a heightened emotional display, such as the shock of receiving terrible news. These interpretations remain completely speculative, however, and it is still not clear whether or not notable trends like the ones observed here and in other studies do indeed reflect some emotional response in the RNG data, and only further study can hope to shed further light on this issue. At their very least, the trends in Jennifer’s data seem to argue that it is worth pursuing further, particularly in the case of solemn group events.

There is one other fitting alternative explanation for the anomalies in Jennifer’s data besides emotion-related group consciousness, and that is they were due to an experimenter effect on my part. As mentioned in the introduction, this issue of whether or not the experimenter might unintentionally affect the results of the study based on their beliefs, wishes, expectations, moods, and even their own latent psi abilities is still one at the forefront of debate within parapsychology (e.g., Kennedy & Taddonio, 1976; White, 1976), and may be especially relevant in this particular study. As also mentioned in the introduction, Jennifer and I were good friends, and her death had affected me very deeply, although I did not show it overtly. This alone might have been a basis for an unconscious mind-matter interaction effect due to repressed emotion, based on the suggestive correlation between emotion and field consciousness effects (e.g., Bierman, 1996; Blasband, 2000). Added to this are any wishes or expectations I may have had regarding the outcome of the results going into the study, although from a personal perspective I must frankly state that I was not sure what I would find in the data at a conscious level. One point that may not be fitting with the idea of an experimenter effect, however, is that at least one potential anomaly in Jennifer’s data (e.g., the 4:30 A.M. extreme peak value seen in Figures 2, 4, 5, & 6) occurred over a day prior to my receiving word of Jennifer’s death, and thus I had no conscious knowledge of it at that time. My personal involvement therefore makes it difficult to know to what degree an experimenter effect might have influenced any of the results here, and for that reason, the interpretation of a possible experimenter effect remains to be a plausible way to account for some (but perhaps not all) the anomalies in Jennifer’s data.

In all, the results reported here do provide suggestive evidence for some kind of anomalous statistical effect on the global RNG/EGG network in relation to the death of Jennifer Sandy. Almost as important as any kind of scientific evidence is the value of meaning. In the obituary that appeared in The Albuquerque Journal on the third anniversary of her death (ABQjournal death notices, 2001), Jennifer’s family had written that her life and the positive influence she brought to people’s lives “...is that ripple in the pond effect that connects us and impacts one life after another.” Perhaps the results of this study represent some basic indication that the effect of which they speak exists through some level of interaction between consciousness and the physical world. It is still not clear whether or not the RNG data do indeed reflect this sort of thing, and only future GCP and field RNG research can hope to shed light on the issues raised here.

I will always miss you, Jennifer.

Acknowledgments

I wish to

thank

Dr. Roger Nelson, the director of the GCP, for technical advice and comments

on

an earlier version of this web paper; and Billie Pyzel,

References (in order of

text

citation):

Nelson, R. D., Bradish, G. J., Dobyns, Y. H., Dunne, B. J., & Jahn, R. G. (1996). FieldREG anomalies in group situations. Journal of Scientific Exploration 10(1), Spring. pp. 111 - 141.

Nelson, R. D., Jahn, R. G., Dunne, B. J., Dobyns, Y. H., & Bradish, G. J. (1998a). FieldREG II: Consciousness field effects: Replications and explorations. Journal of Scientific Exploration 12(3), Autumn. pp. 425 - 454.

Radin,

Nelson, R. D. (2001). Correlation of global events with REG data: An Internet-based, nonlocal anomalies experiment. Journal of Parapsychology 65(3), September. pp. 247 - 271.

Bierman, D. J. (1996). Exploring correlations between local emotional and global emotional events and the behavior of a random number generator. Journal of Scientific Exploration 10(3), Autumn. pp. 363 - 373.

Blasband, R. A. (2000). The ordering of random events by emotional expression. Journal of Scientific Exploration 14(2), Summer. pp. 195 - 216.

Nelson, R. D. (2000). Barry Fenn, 1950 – 2000. Global Consciousness Project exploratory analysis, May 21. Available over the Internet at: http://noosphere.princeton.edu/barry.fenn.html. Downloaded August 28, 2002.

Kennedy, J. E., & Taddonio, J. L. (1976). Experimenter effects in parapsychological research. Journal of Parapsychology 40(1), March. pp. 1 - 33.

White, R. A. (1976). The limits of experimenter influence on psi test results: Can any be set? Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 70(4), October. pp. 333 - 369.

Journal

Staff Report. (1998, August 30). Weekend accidents take three lives: Crash

kills former Sandia High athlete. The Sunday [

Nelson, R. D., Boesch, H., Boller, E., Dobyns, Y., Houtkooper, J., Lettieri, A., Radin, D., Russek, L., Schwartz, G., & Wesch, J. (1998b). Global resonance of consciousness: Princess Diana and Mother Teresa. e-JAP: Electronic Journal of Anomalous Phenomena 98.1.Available over the Internet at: http://www.psy.uva.nl/eJAP. Downloaded March 1999 (Extended abstract also available at http://www.princeton.edu/~rdnelson/diana.html).

ABQjournal death notices [Electronic version]. (2004, August 29). Jennifer Sandy. Available over the Internet at: http://obits.abqjournal.com/results?obit_id=60800. Downloaded September 3, 2004.

ABQjournal death notices [Electronic version]. (2001, August 29). Jennifer Sandy. Available over the Internet at: http://obits.abqjournal.com/results?obit_id=17286. Downloaded August 15, 2002.

Webpage created: September 3, 2002

Revised: August 28, 2003

Updated: September 28, 2004